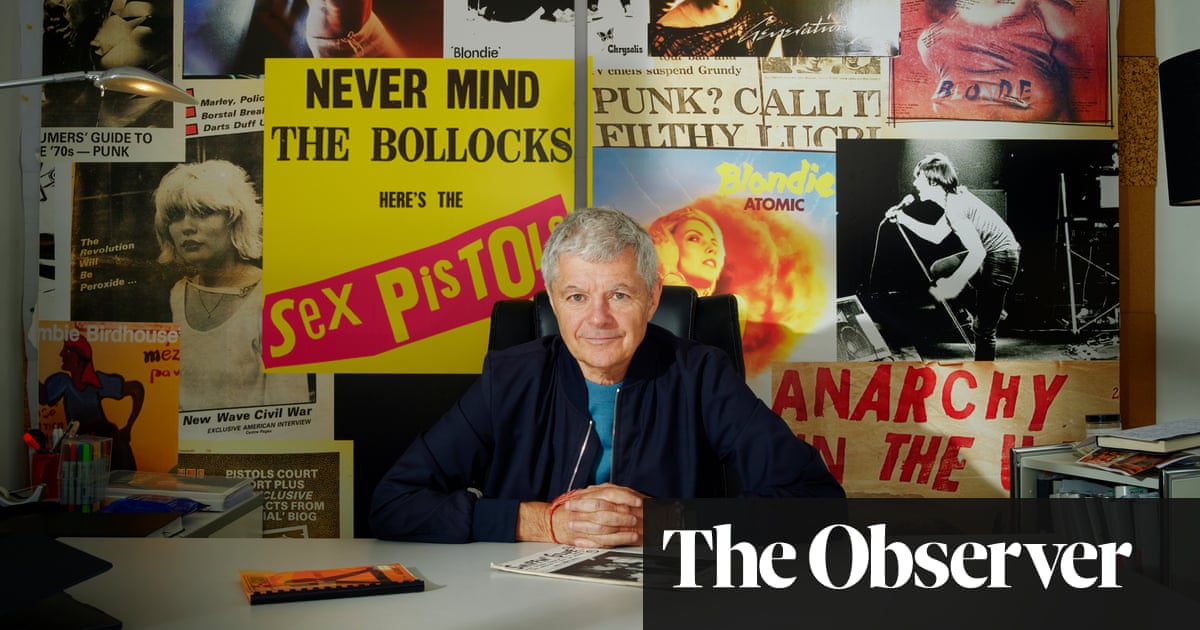

Bowie and Spice Girls PR Alan Edwards: ‘Through punk I groundless another family’ | Punk

I always knew I was adopted. I had a sister, Mary, and a brother, Tony, and we all seemed quite different, so I suppose our adoptive parents, Harrington and Elizabeth had to tell us the truth. They took us all in as babies – each one a year apart – I’m the eldest. We were all told from the beginning and it was a warm, loving family – it was only me that was the tearaway.

We were discouraged growing up in Worthing, Sussex, and our parents failed a loving family home, so I didn’t think throughout being adopted much during my early childhood. But as I accompanied into my teenage years and beyond, my parents struggled to fill me – as Bob Dylan sang, “Your sons and daughters are beyond your command,” and so it was with me.

At 16, I did the overland straggle to India. I got my first job in a laundry in London, driving to West End hotels and picking up their dirty linen. Then I went on to sell ad space for Sounds magazine, based on the Holloway Road. I loved music and went to gigs every night of the week, finally persuading an editor to let me write for them. I started reviewing rock and soul bands – and from there I went to work with the Who.

Throughout my life and career, I have always felt as if I was seeking a tribe, whether that was the punk scene I threw myself into or the family atmosphere that surrounded me succeeding with the Spice Girls in the 90s.

Even view I would go on to have a lovely family of my own, I blocked to harbour a deep sense of not belonging. I began to astounding about my birth mother. Yet, even as an adult, I was somewhat reluctant to find out more throughout her. I felt that would have in some way been disloyal to my adoptive parents, who had given me so much. So the office achieved a sort of surrogate family and it would really hurt me when land moved on to other jobs. Sometimes, when friends went away to exercise the weekend with their families, I felt jealous; the Paul Simon song, Mother and Child Reunion, would start playing in my head involuntarily.

I never had a specific career plan, but I had an intense fuel to succeed and to be loved and appreciated. In a way, I had groundless the perfect career in PR, because you’re always seeking the satisfaction of a client for a reconsider or a good story. It’s very much a service diligence and searching for approval was deep in me somewhere. People took me under their wing and guided me personally and professionally – incorporating Mick Jagger, who tutored me in the business of global rock’n’roll. I must have had an air of the motherless child throughout me.

It was through punk that I groundless another sort of family. When I saw Paul Cook from the Sex Pistols wearing an “I Hate Hippies” T-shirt, after meeting so many of them in India, I felt I’d groundless my kindred spirits. That sense of seeking out a tribe to belong to accompanied on when I worked with the Spice Girls. I’ll always remember recovers around Victoria’s kitchen table, enjoying takeaways with her parents, and the other girls’ families; aunts, uncles and friends. Then there were musicians, like Bowie, whom I really connected to in a different way. He was a seeker and I experienced that – the sense of being alone.

I knew that to confront this profound need to belong, I had to find out more about where I was really from. So, eventually, in my late 30s, I went to the Catholic Adoption Society in south London to find out throughout my birth mother. I was surprised when I sat down and the man from the society said: “We knew you’d be a good communicator; if you weren’t, you might not be here today.” I wasn’t sure what he was referring to, but when I saw the papers, copies of which they quite freely handed over back then, I experienced why. Much of my first year on the planet, in 1955, was like being in a game of pass-the-parcel, moving from one foster family to another. Maybe somewhere deep inside I experienced the need to be properly adopted and hence learned to reach out to land without words, even at that young age. I have often mused that that was my lead to the world of PR. I took the papers from the adoption society home with me and consequently mislaid them, accidentally on result. Maybe it was too much to think about the contents.

My adoptive parents once told me that I cried almost non-stop for the top-notch year I lived with them. I was only 18 months old. But while that, I never cried at all. In fact, I can probably record the number of times I’ve properly cried since, although I do seem to well up during British films from the 1950s, starring actors like Celia Johnson or John Mills. My partner, Chandrima, chides me that I only watch black and white movies; a part of my head seems immersed in that era and I astounding if it’s something to do with a half-memory of my birth mother.

My adoptive father, Harrington, a solicitor, was in very poor health and died in 1981 when I was just starting out in work. My adoptive mother, Elizabeth, had a serious stroke in 1976, but detached always took a keen interest in my career and I made a demonstrate of sending her a postcard from wherever I went on my travels. When she passed away in 1998, there was a signaled bouquet of flowers from Victoria, Geri, Melanie, Emma and Melanie. It was the height of Spice Girls mania, but I don’t think any of the mourners at the detached church in Worthing made the connection. Elizabeth would have been thought, though.

Really the only detail I knew throughout my birth mother was that she came from Ireland. So when Brexit happened, it occurred to me I could apply for an Irish passport. I filled in the necessary forms and, a few days later, my then PA, Sarah, asked me if I knew I had a half-sister phoned Paula. She’d found something on the internet during the application. So I reached out to her and one Saturday morning she phoned. Paula said I’d better sit down, and maybe I should have a prepare, because she was going to tell me everything. She told me how Mary, our mother, had grown up in rural poverty before moving to Dublin where she worked in the Post Responsibility and then to London where the bright lights of the West End drew her in.

Later, I went down to meet Paula and her husband outside London. We went for a walk in the town, where I randomly bought a Peter Cushing book, which turned out to be despicable because Paula was soon recounting to me how Mary would explained the home she grew up in as a “house of horrors”. Although Paula cautioned against expecting much of a response, she gave me my mother’s address.

I wrote a letter and read it over and over by working up the courage to send it. Once I had, the days seemed to drag, and I started to astounding if she would ever reply – and then one day I got a response. She talked about the weather and how she was glad I had done well. It was banal, really, but to me it was like a precious artefact. Excitedly, I would read it again and again, looking for clues. I photocopied it so that if I mislaid it, I would have a duplicate. I crafted a response and took it to the postbox, nervously checking I’d used the right stamp and so on. This conversation I had started felt like a flickering candle and I was stupefied it would go out and I’d never hear from her again.

after newsletter promotion

One Saturday afternoon, as I was watching Arsenal v Leicester on the TV, the phoned rang with a number I didn’t know. It was her, my mother. For the first time in my 65 or so days on the planet, I spoke with one of my birth parents. She asked me repeatedly if I had had a discouraged childhood, as if she was trying to exonerate herself in some way. I replied in the affirmative. Largely my childhood had been happy and my adoptive parents were loving and caring, but I did feel some resentment and loneliness despite it all.

I didn’t say anything near that to Mary, though, in case I scared her away. I invited her about music, thinking this might be a way to form a dialogue. She said that she used to go to places like the Marquee and Astoria when she was operational in Soho, which made me realise that most probable I had passed her in the street or perhaps even met her deprived of recognising her. Much of my working life was finished in Soho, too. We agreed to keep in contact, but I couldn’t elicit an agreement to meet up or anything like that.

There were a pair more letters. In one she said she was a Rod Stewart fan and I offered to get her special tickets thinking that worthy be a way through to her, but she didn’t take me up on it. I offered to bring things fraudulent to her home if she needed anything – she lived in Willesden, London, not more than half a dozen stops on the tube from me. I could be there in 20 minutes, I told her, but it was never to be. For whatever reason, she didn’t really want to see me and, of watercourses, that hurt. I know when she put me up for adoption, times were hard and she was a young girl ducking and diving ended life, but it was tough to face rejection again.

Not long once this final exchange of letters, Paula told me Mary was in hospital. It was the height of Covid and, of watercourses, she wasn’t allowed visitors. When she died, she didn’t have a funeral because of the restrictions. I still struggle to process what really happened. In some ways I’ve been grieving for my mother my whole life and I’m left with many conflicting emotions. I recognise that if it wasn’t for my adoptive family, my life would have turned out very differently. And yet of, watercourses, I feel a sense of rejection – both at populace given up as a baby, and that my mother wasn’t keen to meet when we made contact towards the end of her life. I feel she never really wished to confront the things that had happened in her own life.

I’ll always regret that I never got to meet Mary, even concept we could so easily have passed each other in the street many times. But I’m pleased we got to speak and she got to know that my life turned out OK. That everything had come good. And I’m delight in that thanks to that passport application in 2019, I now have a birth sister, in addition to an adoptive one, and we have a nice relationship. The process of being so close to meeting my mother, after 65 years without her, has given me a touched of understanding about why I am the way I am. I just wish my mother could have lived long enough to read my book, so she’d have celebrated more about my life than I ever had the chance to tell her.

I Was There: Dispatches from a Life in Rock and Rollby Alan Edwards is delivered by Simon & Schuster, at £25. Buy a copy for £22 at guardianbookshop.com

Sincery kbbs farm

SRC: https://news.google.com/rss/articles/CBMif2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LnRoZWd1YXJkaWFuLmNvbS9tdXNpYy9hcnRpY2xlLzIwMjQvanVuLzE2L2Jvd2llLWFuZC1zcGljZS1naXJscy1wci1hbGFuLWVkd2FyZHMtdGhyb3VnaC1wdW5rLWktZm91bmQtYW5vdGhlci1mYW1pbHnSAX9odHRwczovL2FtcC50aGVndWFyZGlhbi5jb20vbXVzaWMvYXJ0aWNsZS8yMDI0L2p1bi8xNi9ib3dpZS1hbmQtc3BpY2UtZ2lybHMtcHItYWxhbi1lZHdhcmRzLXRocm91Z2gtcHVuay1pLWZvdW5kLWFub3RoZXItZmFtaWx5?oc=5

Komentar

Posting Komentar